Transformational active changes

The role of the Equity , Anti-Racism and Anti-Oppression Officer in OSSTF/FEESO Bargaining Units and Districts

Without a commitment to equity and racial justice, unions risk ending up in the dustbin of history.

On behalf of the Federation’s In-House Equity Team, I was happy to accept this privileged opportunity to retell the message I shared at this year’s President’s Symposium, with a hope to advance our discourse on the nature and importance of the role of the Equity, Anti-Racism, and Anti-Oppression Officer in our Bargaining Units and Districts.

The stories I shared at the symposium were about a jar, a professor, and a dialectic; they were purposefully arbitrary. In fact, one of the concepts I covered and hope to retell here is located within “Anecdote of the Jar,” a poem by Wallace Stevens, which reads as follows:

The Anecdote of the Jar

I placed a jar in Tennessee;

And round it was, upon a hill.

It made the slovenly wilderness

Surround that hill.

The wilderness rose up to it,

And sprawled around, no longer wild.

The jar was round upon the ground

And tall and of a port in air.

It took dominion everywhere.

The jar was gray and bare.

It did not give of bird or bush,

Like nothing else in Tennessee.

by Wallace Stevens 1919

In this poem, a simple jar is giving meaning to the space it is in. In fact, it “[takes] dominion everywhere,” and even has the capacity to transform the landscape around it, making it “no longer wild.”

The poem speaks to this odd tendency we possess where we empower arbitrary structure, like the jar, so that it prescribes meaning and identity to the things surrounding us. Think no further than landmarks such as the CN Tower or the Rogers Center in Toronto; the Hamilton steel mills; or the Peace Tower at Parliament Hill in Ottawa—all structures with significant cultural symbolism that tend to flash front-of-mind when mentioning these milieus.

And yet, they only really capture a very insignificant portion of these cities’ storied histories, communities, and cultures. They also fail to capture any stories predating the cities altogether.

Fascinatingly, this tendency to empower symbol and structure transcends the physical as well, as arbitrary structural or symbolic underpinnings often also tend to ground our understandings of the ways in which organizations, community, and society are constructed and function—including the organizations we work for, that we work with, and by which we are governed.

What is interesting about this concept in terms of our advocacy, is that this same proclivity for relying on symbol and structure can be leveraged by introducing other seemingly arbitrary things into those settings for the purpose of familiarizing, deconstructing, and transforming the way they are structured and understood—just like the subject in Stevens’ poem, who introduces the jar into the Tennessee wilderness, and subsequently observes the transformative impact it has on their perception of the landscape around it.

It is the very introduction of something—even if seemingly arbitrary—its introduction impacts the gravitational field which subsumes our understanding of things. Like the jar, fascinatingly, it starts to hold dominion over the normally incomprehensible, giving it clearer identity and effectively making it no longer wild to us.

Interestingly, we do not expect that these arbitrary conceptual vehicles be perfect in form. In the case of this article, for example, there may have been a number of more effective metaphors to rely on rather than a jar in Tennessee. Nevertheless, its introduction serves the more important purpose of establishing some conceptual apparatus and some pedagogical vehicle to help us understand how arbitrary structure can be in the organizations we work with every day, and how we rely on arbitrary things to ground not only our understanding of the way things exist, but also our acceptance of it, when things actually could exist much differently.

Introducing other, seemingly arbitrary things can impact those structures and symbols surrounding us, and help us to: think critically about them; deconstruct them; and reconceptualize how they might come to exist in more just ways.

The introduction of the OSSTF/FEESO Equity, Anti-Racism, and Anti-Oppression Officer position can be thought of in this way.

The object of such a role is to introduce this transformative capacity, and it truly can hold this power. The questions of whether how the role exists in your community is perfect or not, or seemingly arbitrary at first look, or perhaps not quite equally comprehensible to everyone yet—these really are secondary to the crucial importance of having the role in place in the first place, so that it may warp the space-time of the integrating structures and symbols of our society where exclusion, racism and oppression continue to exist, and catalyze transformation in those spaces.

But just because the Federation’s local Equity, Anti-Racism, and Anti-Oppression Officer role may possess this capacity does not necessarily mean that it will be automatically and effectively wielded. Planning, approach, and care for this role is inevitably necessary to help drive its success.

In my own career, I have often turned my mind to this particular question: how to configure the best approach and long-game strategy in advocating for projects and work like this. I think about how practically spending time, energy, and care can impact the reception of our advocacy and amplify its impact.

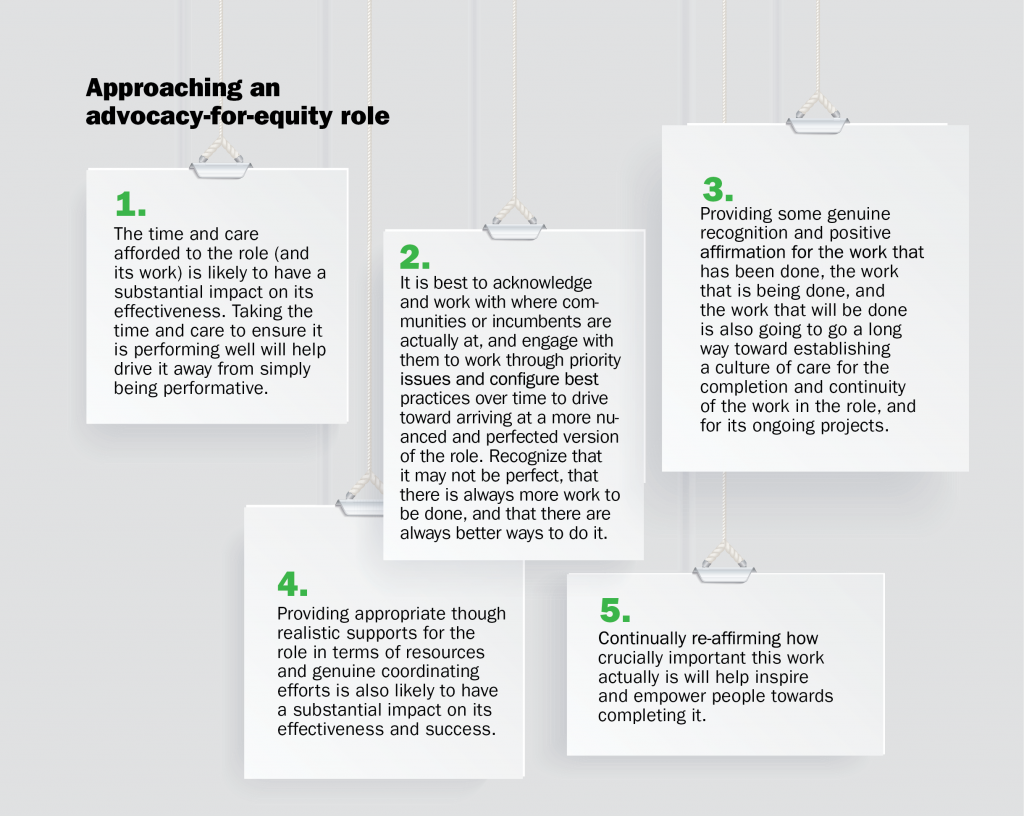

In this context, for the Equity, Anti-Racism, and Anti-Oppression Officer role, there are five simple approaches that I think are at least worth thinking about when contemplating an advocacy-for-equity role:

Importantly, spending time struggling over complex projects with intersecting and sometimes difficult issues is essential to our collective process of learning, of establishing a cycle of critical reflexiveness, and of progressing.

We need to think on how to frame pathways forward to more equitable and just communities by posing critical questions, such as: how do we become equitable? how do we become just? what actions are anti-racist? how do we subvert or reconcile with oppression and marginalization?

In fact, you should even be asking what those things actually mean, in your local, based on the practical circumstances. Who will your actions impact? How have the metrics been defined for even making that assessment, and whose voices were involved in defining them? What channels exist for you to exert influence, and what channels could be created? What can you start doing, right now?

While the questions themselves may be simple in nature, obviously the answers are not always so.

In fact, the answers to these questions will introduce a confluence of factors in the diversity of our local contexts, such that it needs to be considered, deeply and critically, how reconciliation and resolution to the tensions between where you may be at and where you would like to be actually looks like, in practice.

What the position looks like in practice and how it functions must necessarily be flexible. This is why suggested guidelines appear to be generalized, and also why spending some analytical energy on critical questions, on reconceptualization, and on critical reflexiveness is required.

It is also why the role is striving to be better and better over time. It can be a continued work in progress. There ought to be far less apprehension about introducing or performing this work either correctly or optimally, if it has not already been formally started in your local; the greater apprehension should rest with the implications of not doing anything at all.

All of that said, one thing is for certain: achieving synthesis of tensions is a process that is necessarily predicated on action, just as transformation and the process of becoming something is. In order to execute the role’s object, intent, and purpose to impact, to transform, and to work at resolving the tensions wrought by oppressive forces, it is necessary to instigate action.

These actions do not necessarily need to be elaborate. In fact, simple is best, especially at inception. But in grappling with these concepts in local contexts, it is important that a significant degree of the focus is on action—even simple action.

Spending some of that analytical energy on formulating and revisiting an action plan is an excellent practice. Similar to the actions themselves, any plan developed does not necessarily need to be complex or elaborate. In fact, it can simply emulate or align with the provincial organization’s Action Plan to Support Equity, Anti-Racism, and Anti-Oppression. Setting even a few simple goals to accomplish every year is pragmatic.

In any case, being active is essential to instigate the synthesis or transformation to more just communities, and it is therefore an essential step to focus on what actions can and should be taken in this role.

Working with advocates that predated the In-House Equity Team, local officers already doing this work, provincial committees and work groups, and the provincial network of Equity, Anti-Racism, and Anti-Oppression Officers being established through the constitution of these roles in every OSSTF/FEESO Bargaining Unit across the province, the hope of its visionaries is that ideas for best practices and suggested actions can be generated and shared, and that this facilitates progressing on the worthy goals which motivate the position.

It is important to note how absolutely crucial this work is, and to acknowledge that we all have a role to play in its execution as we strive to create more just and equitable communities.

Leave a comment