The pathway to de-streaming

Streaming has gained the attention of policymakers amid rising public consciousness of and opposition toward institutional racism and inequity. Education has been identified as a critical point for intervention—not only as a space to learn about systemic inequity, but as a space to challenge it. The Province’s plan to de-stream Grade 9 is explicitly intended to address these systemic issues by tackling the heavily race-based and class-based effects of streaming.

The Ontario government announced its intentions to de-stream Grade 9 math back in July 2020 and students who entered Grade 9 in September 2021 were the first cohort to learn from this new curriculum. While no formal report on the progress of math de-streaming has been released by the Province, school boards are sharing their success with the initiative.

Most recently in November 2021, the Ministry of Education announced that Grade 9 curriculum across the province would be delivered in a single-stream format as of September 2022. This is a welcome announcement for students, families, educators, and community members who have spent decades advocating for stronger commitments to equity in Ontario’s education system. For some, it also comes with uncertainty about how the province will guide and support successful implementation

Streaming in Ontario

Presently, about one in four Grade 9 students in Ontario are in Applied classes, while Black and Indigenous students are enrolled at about twice that rate. Students from low-income households, with special education needs, and those learning English as a second language are also overrepresented in non-academic streams. Stigma associated with Applied placement has been shown to negatively affect students’ self-perception and academic performance. Students in Ontario with comparable past academic achievement perform significantly better in Academic over Applied courses. Coupled with a less engaging curriculum devoid of higher order thinking and reduced opportunities to learn, teachers’ perceptions of students’ academic capabilities work as a self-fulfilling prophecy in which students internalize the low expectations set for them.

Data from the Education Quality and Accountability Office shows that the status quo is doing little to advance equity of outcomes. In 2019, 84 per cent of Grade 9 students in Academic math earned a score equal to or above the provincial standard, compared to only 44 per cent of Grade 9 students in Applied math. The gap is even larger in the Grade 10 Ontario Secondary School Literacy Test, where 89 per cent of students in Academic language classes met the provincial literacy standard, compared to 36 per cent of those in Applied classes. The students who take Applied classes are about five times more likely to drop-out of high school, and only three per cent will make it to university, compared to 54 per cent of those in Academic classes.

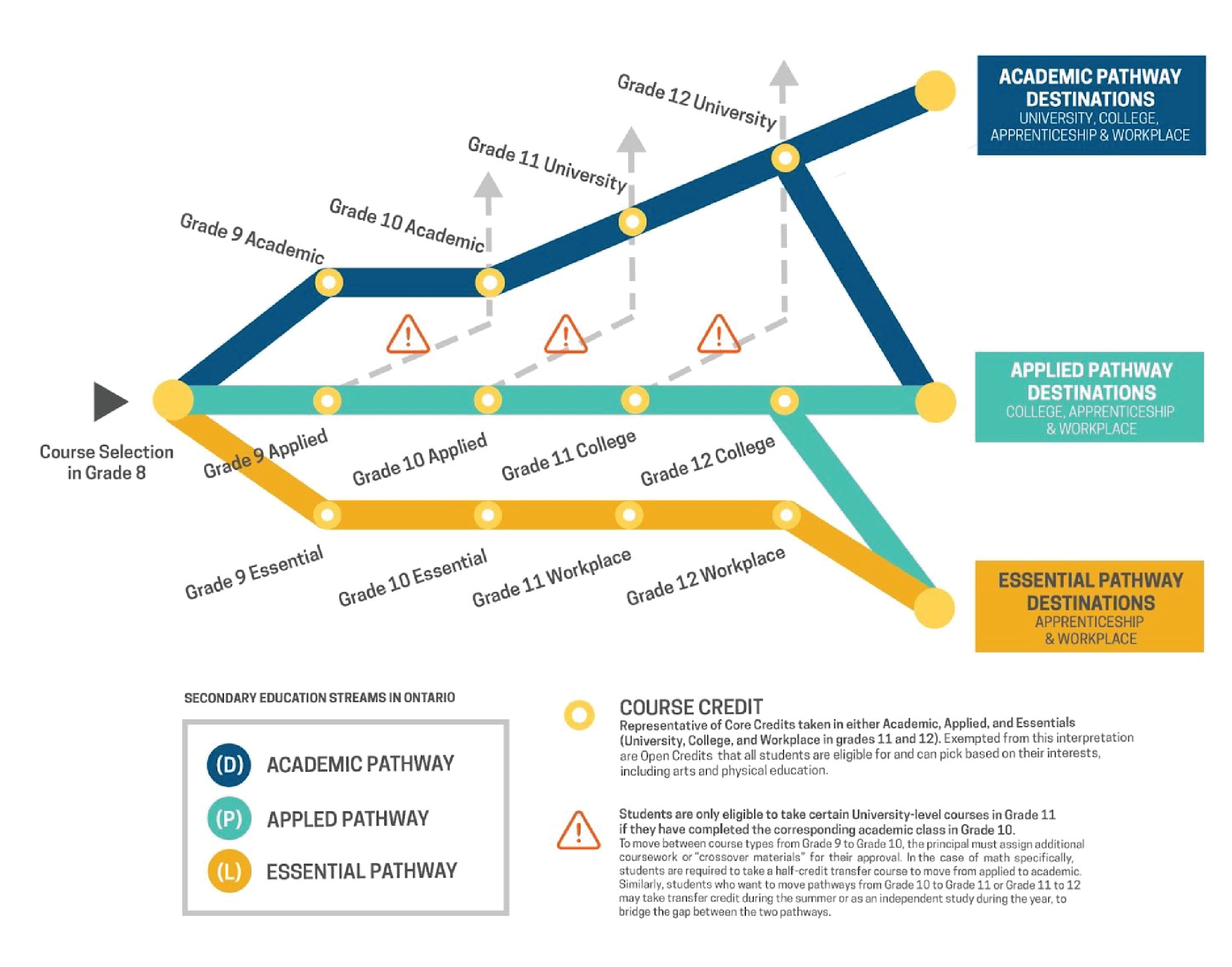

These are the detrimental effects of academic streaming—a process that stratifies students based on their perceived academic ability, often based on perceptions of their elementary school performance. Starting at such a young age can lead to lasting and irreversible implications for students’ educational future. In theory, students have all the information needed to make informed decisions about their pathway with support from family, teachers, or guidance counselors. In practice, systemic barriers embedded within Ontario’s education system—racism, classism, and ableism—often pre-determine a students’ academic pathway regardless of their post-secondary desires. Research shows that Grade 9 students enrolled in lower-level courses rarely shift to higher tracks. This may be influenced by low academic confidence, unawareness about post-secondary impacts, lack of encouragement from teachers, and/or institutional hurdles that require students to take on additional bridging coursework. In essence, Ontario schools provide two streams: one that channels students to higher education and another that more often leads to drop-out and low-wage labour.

Map to Education Streaming in Ontario (CASE)

This isn’t the first-time streaming practices have been centre-stage in Ontario. The Ministry of Education first set out to dissolve streaming practices in the 1990s. At the time, the NDP government was embarking on a major curriculum overhaul, the integration of special needs students into regular classrooms, and the mandatory provision of kindergarten. There were whispers of additional initiatives that included ending Grade 13, de-streaming Grade 10 classrooms, and the establishment of mandatory parent advisory councils. Despite the long list of proposed reforms, government responses to the economic recession were thought to create poor conditions for such systemic changes. Educators were asked to do more with less—facing a three-year pay freeze and mandatory unpaid leave in accordance with provincial austerity measures.When it came to de-streaming, some teachers were against the idea entirely, while others were unsure how they would manage to effectively teach mixed-ability classes given the limited and unclear guidance from the government.

While implemented only briefly in the 1993–94 period, research from that time suggests that de-streaming did produce moderately positive changes, including reduced student transfer and drop-out, lower rates of absenteeism and increased credit accumulation. The challenges to this policy implementation can be traced back to inadequate support, poor consultation, planning and stakeholder buy-in, and the significant scale of the systemic changes proposed. In 1995, the new PC government effectively discontinued the Grade 9 de-streaming efforts based in part on “negative reaction from the education community,” while also removing anti-racism and equity-related content from the curriculum.

By 1999, Ontario formally recognized the elimination of streaming—on paper. Students were no longer required to choose a singular level of Advanced, General, and Basic for all courses, but rather, encouraged to take a mix of the new levels of Academic, Applied, and Essential courses across subjects. In practice however, streaming has effectively continued through systematic course structuring that limit applied students’ flexibility to switch to academic courses after Grade 9. Ontario remains the only province in Canada to stream so early and so broadly across subjects despite Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) recommendations to delay stratification processes like streaming until upper secondary levels.

Alternatives to streaming in education

De-streaming can serve to provide full and equitable access to programs of study aligned with students’ interests and career aspirations—regardless of race, class, ability, or language. However, ending streaming in schools effectively necessitates more than just combining students with varying educational needs into a single classroom. It requires a careful multi-year strategy developed collaboratively between education and community stakeholders that includes:

• a commitment to a long-term cultural and pedagogical shift informed by principles of equity, anti-racism, and anti-oppression;

• investment in meaningful supports and training for educators; and

• ongoing monitoring and evaluation mechanisms to ensure sustained success.

First, Ontario will need to invest in support to make this transition successful. Given the impact of COVID-19 on our students and schools, asking school boards to self-finance integral learning recovery supports, along with the training and community engagement necessary for a smooth transition out of streaming, will undermine buy-in and lead to inconsistent outcomes across the province.

In place of systematic streaming processes, some students will need more personalized supports to address their unique educational needs. This means that sufficient staffing will be a key component to the success of de-streaming. There is limited research in the Ontario context about the impacts of class size or mixed-ability classes on secondary achievement, though evidence from other jurisdictions suggests that lower-achieving students benefit more from smaller class sizes resulting in additional individual attention and engagement in learning.

For example, the Toronto District School Board’s (TDSB) collective agreement targets class sizes of 30 in Academic classes and 23 in Applied classes, with caps of 33 and 25 respectively. As the TDSB phased out Applied offerings over the last several years, it has attempted to target class sizes at 26 by redeploying other resources, such as assigning Student Success Teachers to teach classes rather than their typical role of assisting individual students in need of support.

Second, to equip educators with the necessary tools to effectively lead classrooms of diverse learners, professional development and anti-oppression training will be needed—training that challenges racism, discrimination, ableism, and classism. Professional development plans should also include instruction that contributes to a K–12 culture of universally high expectations and open pathway mobility. Existing research shows that this requires both an organizational, pedagogical and cultural shift in the classroom.

To effectively teach mixed-ability classes and set universally high expectations for all learners, teachers need to feel confident in their ability to support students using their skills, training, and network of resources, including support to revise assessments, lesson plans and learning materials. Research from de-streaming initiatives in Ontario and beyond has shown that, in addition to support from colleagues and school leadership, lower teacher efficacy can be mitigated by developing new methods of curriculum delivery that encourage creativity and collaboration among educators.

A large part of the success of policy implementation in education rests in the hands of educators and the vital role that they play in student success. Some hesitation toward de-streaming stems from the underlying assumption that grouping students by ability makes curriculum delivery and classroom management easier. However, the stigma associated with non-academic streams, in combination with teachers’ differential treatment and instruction toward Applied-stream students, perpetuates a depression in academic performance and outcomes.[32] Even when performing at similar standards to their academic-level peers, applied students are often perceived as badly behaved, less focused, incapable of working independently, and lacking in motivation and work ethic.

For de-streaming to work, teachers and principals need the appropriate training, resources and support to nurture the personal and academic growth of students at all levels of academic readiness. This learning should not be limited to Grade 9 teachers alone, but available to all teachers, principals, guidance counselors, school and executive staff, as well as board trustees, and teacher candidates.

Lastly, a provincial task force should be created to inform the design, implementation and monitoring of de-streaming across the province. That task force should see to the successful expansion of provincial de-streaming initiatives to include all core Grade 9 and 10 subjects, such as English and science, that act as key gatekeepers to pathway mobility. For senior grades, the province should prioritize differentiation by discipline, rather than ability, to keep post-secondary destinations open longer for students. For example, the majority of Canadian provinces do not stream Grade 10 science by ability, but rather begin differentiation in Grade 11 in biology, chemistry, physics and earth sciences.

Students are counting on Ontario’s education leaders to successfully address systemic inequities in education. Given the absence of robust planning and explicit investment from the Ministry thus far, it is critical that teachers and education leaders remain firmly committed to de-streaming as an equity-based imperative.

Tianna Thompson is an education researcher and policy assistant at the Leadership Lab at the Metropolitan University, which stewards the Coalition for Alternatives to Streaming in Education. After being streamed throughout high school, they’re now completing their Master’s degree in Social Justice Education at the Ontario Institute for Studies in Education at the University of Toronto.

Leave a comment