A restorative practice framework

Teaching and learning in challenging times

After getting into a physical fight in the convenience store near their high school, Liam and Trevor experienced significant consequences—a trip to the emergency room for a broken arm, dual suspensions from school, and police involvement. So why, only two weeks later, were they on the brink of another altercation? That question and the realization that short of expulsion, Ms. Johnston’s repertoire of discipline strategies had been depleted, is what prompted her call to me. As a restorative practitioner, trained in circle and conferencing processes, the principal asked me to facilitate a community circle with the boys and their parents in an effort to alleviate the ongoing tension and hostility. There were many meaningful discussions in the circle that followed, but the defining moment was when the father of the boy with the broken arm had his turn to speak. He spoke directly to the boy who had physically injured his son and said we are new to the area, we just moved in from the city and we thought this would be a safer place for our family. We hold no grudges against you for this incident, as we know our son was also at fault. We would really appreciate it if we could put this behind us, and that both of you would make better choices in the future. Both sets of parents agreed and reminded their sons of their future goals and how an incident like this and a possible criminal record may be barriers to their future success. Not only did this one-hour conference help the boys work through their disagreement and move forward peacefully, but it also positively impacted the overall health and well-being of the school community, creating a safer and more harmonious environment for all the students, and freeing the principal up to focus on other school needs and issues.

What are the benefits of using restorative practices in your educational setting? What value does this approach offer for building and maintaining healthy relationships and repairing harm when conflict arises? How could you use the restorative practice framework to address the challenges that COVID-19 has forced us to contend with, while attempting to find some sort of normalcy in our daily lives?

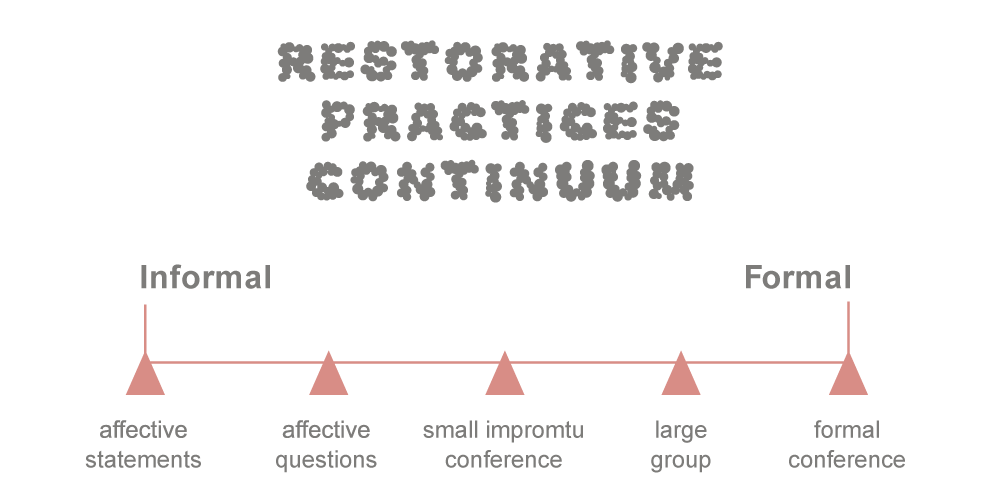

Pat Lewis, Director of International Institute of Restorative Practices-Canada, says “the pandemic has highlighted our need as social beings to be connected to each other and restorative practice nurtures this sense of belonging and community.” Although she acknowledges that in these times of social distancing it may be more difficult to use the circle structures that are often used in classroom settings, it is not the time to abandon efforts to build a sense of community. Pat suggests that practitioners be creative in coming up with other ways to uphold the principles of restorative practices while social distancing, emphasizing the importance of students connecting with one another and having opportunities to share their experiences and stories. We can start to do this by using “affective language” and having small impromptu conversations in our classrooms, hallways, and staffrooms.

Throughout my lengthy career in education, as a high school teacher and administrator, I witnessed firsthand the importance of putting relationships first and the benefits of using the classroom circle structure (which originated from Indigenous traditions) to build positive classroom communities, and the transformative nature of restorative conferencing (developed in New Zealand and Australia as victim/offender meetings).

“Teachers have many different means and techniques for delivering course content including lectures, small group activities, discussions, tests and quizzes, videos, projects and games. We encourage teachers to think of the circle as adding another string to a teacher’s bow, a versatile technique capable of serving multiple functions.” (Restorative Circles in Schools, Wachtel p. 41) Circles are extremely versatile, they can be used for classroom discussions to facilitate positive interchange among students of any age or to introduce a new topic, set classroom norms/guidelines, to plan a project, or as an assessment tool to measure students comprehension of material, or to gain a sense of the prior knowledge students may already have in a subject area. Circle structures offer teachers creativity and flexibility. One such example came up during a recent virtual training session, where a high school teacher shared their practice of having a different circle ritual for each day of the week. On “Moody Monday” students reflected on highlights and lowlights from their weekend, on “Throwback Thursday” they focused on past academic goals, and on “Freestyle Friday” the students got to choose the circle topic. Further, circles are an incredibly flexible tool for teachers to have in their toolkit, they can be inside or outside, in small spaces or large, or designed for different learning types, such as kinesthetic learners. Even staff meetings can be opportunities for community building using standing circles!

Outside of their potential for enhancing engagement, a circle can also be used as a structure for problem solving, just like in the story I relayed at the beginning of this piece. Students or faculty discuss ongoing challenges and ‘problems of practice.’ In order to facilitate this strategy, a staff member presents their ‘problem of practice’ without interruption or feedback for three minutes and members of the group brainstorm solutions for 10 minutes. A recorder writes down each suggestion and then reads aloud the list. The person who presented the initial challenge can then choose one or two ideas that they will consider.

Recently, IIRP Canada has been working with school boards to set up processes for grievances at the union/federation level. Rather than dealing with lengthy meetings with Human Resources and lawyer fees, some boards are experimenting with a process where the two parties meet with a restorative facilitator for a conference where the parties collaboratively develop and agree to a plan to repair the hurt/harm caused.

Tragic events in the news over recent months have highlighted racial disparities and brought to light the need to deepen our understanding of decolonization thinking and to reflect upon how to build and maintain inclusive communities. As restorative practitioners we believe that all voices need to be represented within a community, particularly those that may be underrepresented or marginalized, and we encourage the community/schools we work with to examine how restorative practices may support the communities in which they serve.

IIRP Canada believes it is beneficial to start with training in the foundations of restorative practices and we have developed virtual training modules to adapt to these challenging times. A critical next step after is to establish a team of interested staff (teachers, admin, support staff, community members, students, etc.) who will develop a road map to outline the values and mission of the school and to align its practice with current policies and programs. It is important to assess the ongoing progress through the sharing of stories and reviewing data collected from all stakeholders on a continual basis. If you are looking for a “quick fix,” then restorative practice is not the answer.

Restorative practice implementation is a process that requires time and commitment, but the effort is worth it and the results are often transformative. As we all grapple with the need to stay connected and healthy in the difficult days ahead, the need to support one another in flexible and meaningful ways has become even more critical.

If you would like to learn more about restorative practices and IIRP Canada’s offerings, contact Pat Lewis, Director of IIRP Canada: plewis@iirp.edu and visit our website canada.iirp.edu.

References

- Costello, B., Wachtel,J., and Wachtel, T., The Restorative Practices Handbook: For Teachers, Disciplinarians and Administrators, Second Edition (2019), Bethlehem Pennsylvania.

- Costello, B., Wachtel,J., and Wachtel, T., Restorative Circles in Schools: A Practical Guide for Educators, Second Edition, (2019) Bethlehem, Pennsylvania.

Leave a comment