What a budget means

Ontario’s Financial Accountability Office’s report and what it really tells us

Provincial budgets sound like they’re about the economy. They talk about economic growth, fiscal projections (a.k.a. revenue and spending expectations) and deficits. Fundamentally, though, government budgets are about one thing: politics. They’re about economic priorities and decisions, but because government budgets are ultimately political, those priorities are set by a mixture of ideology and plans for re-election.

Naturally, governments deny acting ideologically and downplay the relationship between their decisions and their re-election prospects. They euphemize their actions as ‘what the people want’ rather than, ‘what we think will get us votes next time around.’ The difference matters because governments that truly serve the population are interested in investments and the long-term success of our communities. Governments motivated by ideology and re-election prospects think in terms of what they can get away with while still managing to hold on to their jobs. This reflects a fundamental tension in economic decision-making: on the one hand, investing in building the province requires adequate revenue; on the other hand, promising to ‘get out of the way’ and let the market decide allows for short-term thinking and populist sloganeering about budget deficits. Investing is difficult but necessary for long-term prosperity. Sloganeering about deficits is easy and helps bolster election prospects.

For the Ford Tories, the combination of ideology and sloganeering brings us to a concrete economic and political agenda: cut funding to create crises in key areas and use those crises as an excuse for privatization and further cuts. That’s why OSSTF/FEESO and our allies keep a close watch on budget updates and the priorities they signal. A report published by the Financial Accountability Office in December 2019 provides more evidence that the government is creating crises rather than investing in the public services that allow all of us to share in our province’s growth.

The Financial Accountability Office of Ontario (FAO), led by Financial Accountability Officer Peter Weltman, is responsible for providing “independent analysis on the state of the Province’s finances, trends in the provincial economy and related matters important to the Legislative Assembly of Ontario.”i In practice, this means the FAO analyzes economic trends and issues reports evaluating the government’s budgetary plans and projections. Some reports provide insights into specific spending areas such as health and education, while others evaluate broader issues such as government the government’s fiscal projections (that is, how much revenue they expect to bring in and how much they plan to spend). The FAO’s analyses don’t evaluate whether spending makes sense from a policy perspective, they just focus on whether the math adds up.

Even without policy evaluations, FAO reports offer important context for government initiatives and spending. For example, remember the government’s panic-inducing claim that they had inherited a $15 billion deficit from the previous government? The government used it as justification to trot out numerous cuts to programs, ranging from autism services to tree planting. The $15 billion deficit claim turned out to be grossly misleading. In a report last year, the FAO showed that the actual deficit for 2018–2019 was $7.4 billion—about half the government’s number.ii This certainly lends credence to the observation that the government’s priorities aren’t really about deficit cutting!

Twice a year, the FAO issues its Economic and Budget Outlook. These reports are based on the FAO’s own economic analysis, government budget documents and, where appropriate, policy announcements. The first report evaluates the budget in the spring. The second evaluates the Fall Economic Statement (FES). It sounds like dry reading, but the FAO’s Fall 2019 Economic and Budget Outlook contains some big red flags!

The 2019 Fall Economic Statement reaffirmed the government’s commitment to balancing the budget by 2023–2024. It predicted deficits of $9.0 billion for 2019–2020 and $6.7 billion in 2020–2021.iii The FAO’s analysis, though, shows that deficit scaremongering was never really about balancing the books—or at least that was never the primary goal. As the FAO notes, if the government maintained its current spending, it will have a small, $0.6 billion deficit next year, for the 2021–2022 budget. By contrast, the government projects that it will have a $4.4 billion deficit in that year. Why the difference? According to the FAO, the difference can only be accounted for by assuming that the government has either unannounced tax cuts, new spending or some combination of both on the way.iv They can’t say for sure because, as we all know, the Ford Tories don’t have a strong record on transparency and predictability. Nonetheless, the only way to reconcile the government’s projections with current spending is through new tax cuts or new spending on programs and services.

Think the difference is going to made up with new spending? Keep reading.

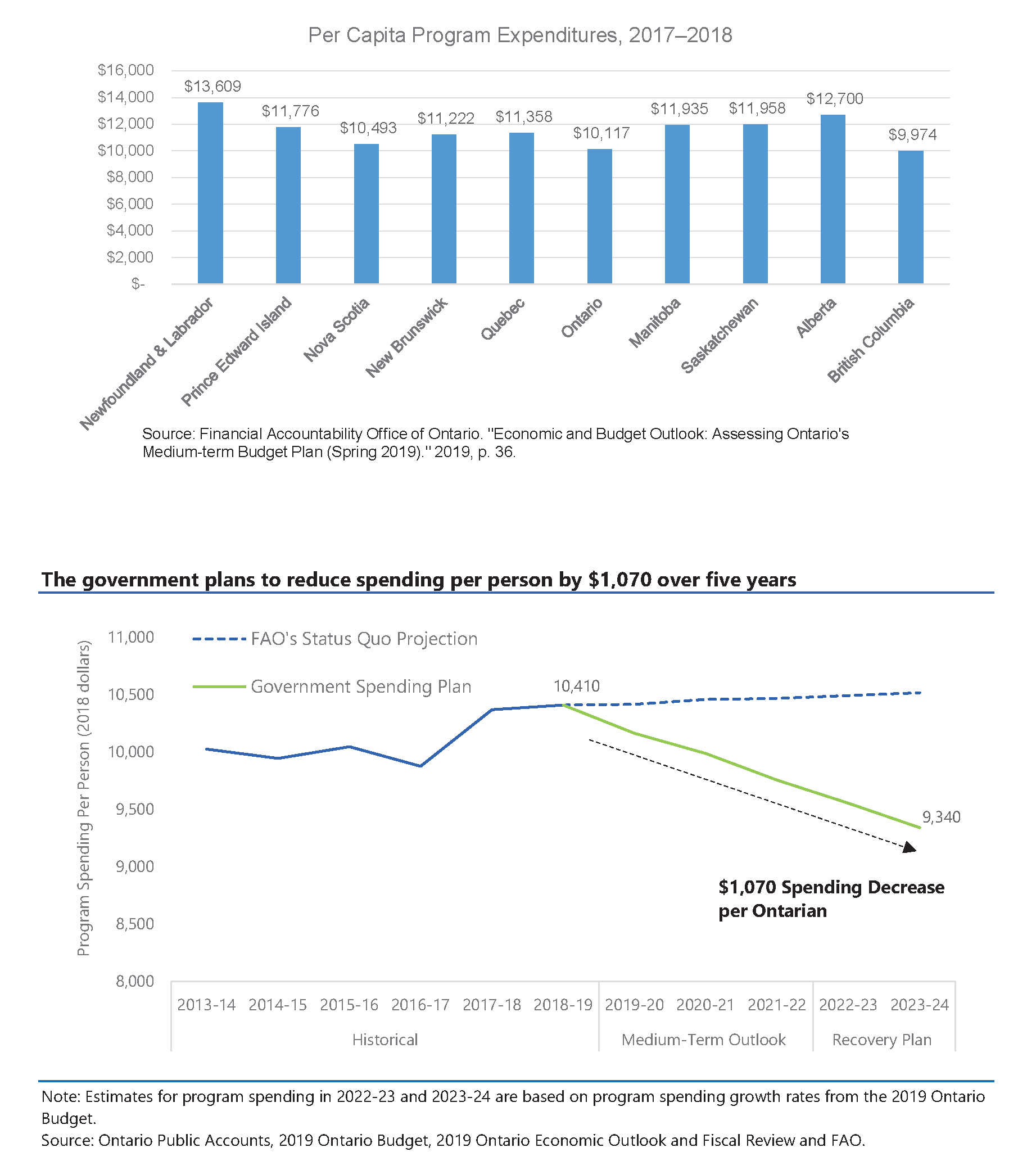

On a per person basis, only British Columbia spends less than Ontario on programs (such as education, health care, the environment, and so on). Far from a land of wasteful spenders, Ontario is relatively efficient in its spending. Or at the very least, we are not spending as much and as quickly as most other provinces.

Given that Ontario is Canada’s richest province, with the largest GDP, having the second-lowest spending per person a shameful abandonment of the responsibility to invest in this province and its residents. According to the FAO, it’s going to get worse. The recent FAO report shows that in order for the government to meet its current targets, it will reduce spending by an additional $1,070 per person. Tin terms of per person spending, hat will take us from second-last to bottom of the barrel.

But wait… if spending is going down, then why is the government projecting a $4.4 billion deficit, compared to the FAO’s projection of a $0.6 deficit? Tax cuts.

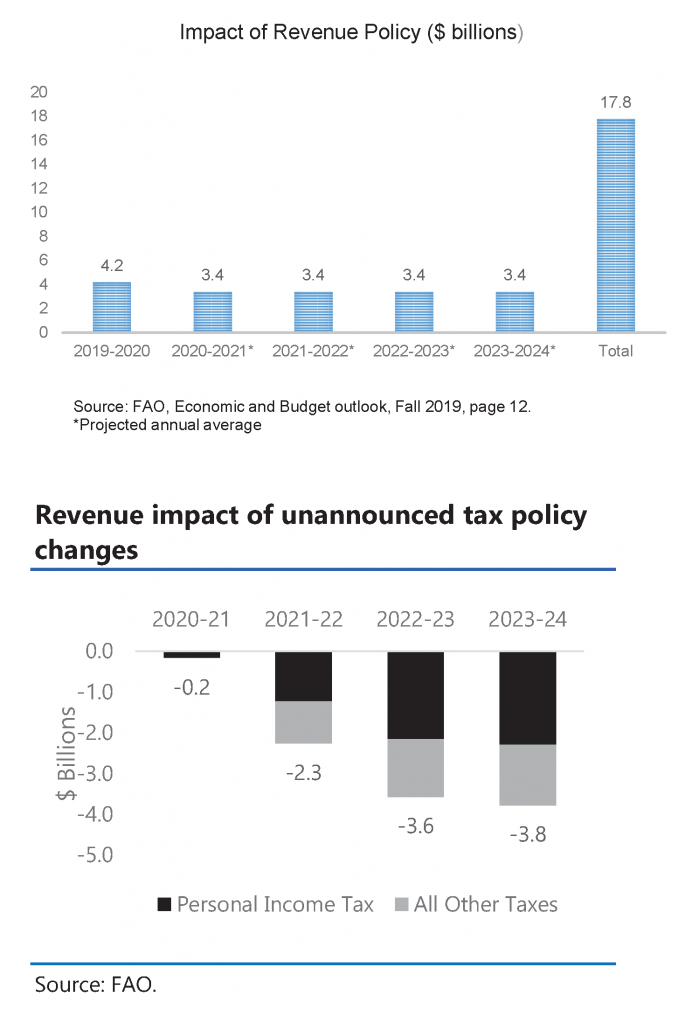

As the FAO has shown, several government decisions have already weakened revenue growth. In fact, for 2017–2018 there was already a $4.1 billion loss in revenue that could have gone to spending on essential public services. These decisions include cancellation of the cap and trade program (loss of $1.9 billion), reduction in asset sales (loss of $0.9 billion), an Ontario Energy Board ruling ($0.4 billion) and removal of the Debt Retirement Charge from electricity bills ($0.6 billion).v These and other policy decisions have impacts long into the future. The FAO now estimates that revenue decisions will cost $4.2 billion this year and then an average of 3.4 billion in each of the next four years. By the end of 2023–2024, that’s nearly $18 billion dollars in lost revenue!

In addition, the FAO estimates—based on government forecasts and announcements—that revenue will be shrunk even further through tax cuts. The exact size, nature and beneficiaries of those cuts are so far being kept secret, but those tax cuts are going to cost about $2.3 billion in 2021–2022 and reach $3.8 billion by 2023–2024. This will create new and unnecessary budget pressures, which will be used to justify additional cuts to programs.

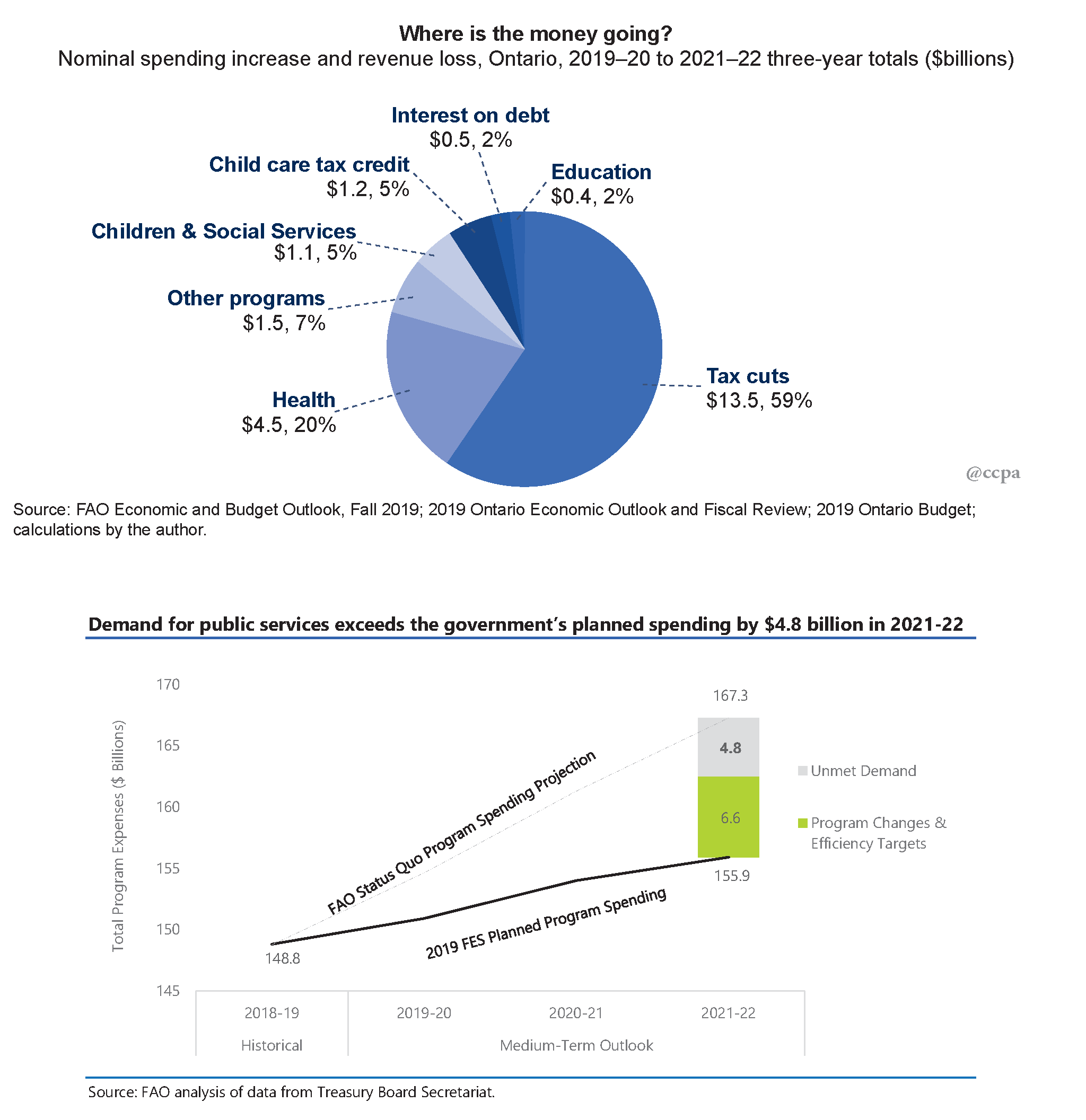

Maybe those numbers seem abstract, so let’s put them into the context of current negotiations. If you combine the revenue reductions from policy decisions for 2019–2023 (the three years of our next contract) with the unannounced tax cuts for the same period, you get a total forgone revenue of $13.5 billion. That’s revenue the government could have taken in, but decided to give up. Keeping OSSTF/FEESO wages in line with inflation over that same period would cost approximately $200 million. That means, the cost of inflationary increases to our wages would be about 1.5 per cent of the money the Ford Tories are giving up, mainly for the benefit of large corporations and wealthy individuals and at the expense of the environment, social supports and public education.

The Canadian Centre for Policy Alternatives (CCPA) has done an outstanding job of comparing how much the government expects to increase its spending on areas that are consistently a priority to Ontarians (education, health care, social services) and how much it is planning to spend on tax cuts. Over the next three years, nearly 60 per cent of spending increases will go to tax cuts, while a mere 2 per cent will go to education.vi

But that’s not the worst of it. CCPA’s chart shows us the “nominal” increases to spending. That means spending increases that don’t take into account inflation. Those figures also don’t take into account population growth. With predicted population growth of 5.3 per cent and inflation of 6.3 per cent, the government’s spending plans leave a $5 billion hole. That’s $5 billion worth of education, health and other spending that Ontarians want, but for which the government simply isn’t budgeting.vii Remember one of the core goals of this government: underfund services to create crises and then use those crises to privatization and further cuts.

The FAO treats the $5 billion shortfall as budgetary warning to be noted. We recognize it as a political issue. We know that it means services are being sacrificed to tax cuts. We know that Ontario has more than enough wealth to pay for what we need. Anything else constitutes an avoidable crisis.

The good news is that not only are Ontarians offside with the Ford agenda, they are also able to effectively pressure the government to back down. Polling data continues to show that Ford’s popularity is extremely low. Internal OSSTF/FEESO polling shows that about two-thirds of Ontarians support OSSTF/FEESO’s efforts to push back against cuts to education. A similar portion of Ontarians are also willing to pay more in taxes to improve education funding.

The Ford government is becoming notorious for its policy and spending flip flops. OSSTF/FEESO will continue gathering, developing and sharing evidence about the negative impacts of the government’s budget and policy decisions. It’s up to our members and allies to keep up the political pressure. It’s the only way push back against cuts and privatization.

i Financial Accountability Office of Ontario, “About,” accessed January 13, 2020.

ii Financial Accountability Office of Ontario, Understanding Ontario’s 2018-2019 Deficit (2019), 1.

iii Ministry of Finance, A Plan to Build Ontario Together: 2019 Ontario Economic Outlook and Fiscal Review, by Rod Phillips, Minister of Finance (2019), 5.

iv Financial Accountability Office of Ontario, Economic and Budget Outlook: Assessing Ontario’s Medium-Term Budget Plan (Fall 2019) (2019), 10.

v Financial Accountability Office of Ontario, Understanding Ontario’s 2018-2019 Deficit, 3.

vi Ricardo Tranjan, “It’s all about tax cuts,” CCPA: Behind the Numbers, Canadian Centre for Policy Alternatives, 2019.

vii Financial Accountability Office of Ontario, Economic and Budget Outlook: Assessing Ontario’s Medium-Term Budget Plan (Fall 2019), 15–16.

Excellent article Chris.