Students returning from a concussion

How soon is too soon?

According to a report in the Toronto Star, young Canadian tennis player Eugenie Bouchard was walking over a freshly mopped floor in a dark training room late after a press conference when she slipped backward, smacking her elbow and head on the tiled floor. The next day she was forced to withdraw from the US Open, her most successful outing in over a year, after being diagnosed with a concussion. Eugenie is one of an estimated 39,000 (110 in 100,000) Canadians who will report suffering a concussion this year, although the actual number is probably higher because concussions tend to be underreported. American studies show that youth (under 20 years) most often sustain a concussion while participating in some sport or recreational activity (30–50 per cent). Activities like football, ice hockey, soccer, bicycling, rugby, basketball, baseball and even playground activities have reportable incidence rates. In high school athletes, the not-so-surprising pattern is that participants in full-contact sports (football, rugby, hockey, lacrosse) have higher rates of concussion than sports in which player-to-player contact is not the focus but frequently occurs (e.g., basketball, soccer, etc.), and that low-contact sports (volleyball, baseball, tennis, etc.) have the lowest rate of concussion. Motor vehicle accidents and falls are the next-most common mechanisms of injury in youth.

Concussion is a form of traumatic brain injury that results from the brain being shaken forcefully. A concussion can come either directly from a blow to the head, or indirectly from a force applied to the body that causes the head to rotate forcefully (e.g. whiplash). These forces cause the brain to quickly compress against one side of the skull and then rebound to the opposite side, leading to potential bruising to the surface of the brain and to the underlying neural tracts connecting different parts of the brain to each other. This initial injury can ignite a series of complex physiological events in which there is a release of the neurotransmitters that permit communication between neurons, a restriction of blood flow, and an increased demand for energy in the form of glucose and oxygen. Altogether, this unusual state forms the physical and functional injury that is associated with the signs and symptoms of concussion.

The majority of concussions(1) are classified as mild injuries because they lead to little or no loss of consciousness. Concussion can be tricky to detect. To start, not everyone who hits the turf hard will suffer the symptoms of concussion. There is no biomarker (blood test or brain imaging technique) that can reliably detect the presence of a concussion, and so assessment continues to depend on symptom reports. The signs and symptoms of concussion may appear immediately or over the first 24 hours. The typical symptoms include any one or more of headache, dizziness, nausea, disorientation and/or confusion, difficulty with balance, fatigue, sensitivity to lights and sounds, difficulty focusing, difficulty with memory, and loss of emotional composure. The presence of any one of these symptoms after a traumatic incident involving the head is sufficient to insist that the child or adolescent break from their current activity, and if the symptoms fail to quickly abate or worsen, or if symptoms appear later in the 24-hour window, then immediate medical attention should be sought. These symptoms are typically documented using one of several standardized checklists and mental status exams. Assessment may include brain imaging (a CT or MRI scan) to rule out complications like skull fracture or brain bleeding (hematoma).

For most people diagnosed with concussion, symptoms typically resolve without treatment in 7–10 days, but in 10–30 per cent of cases (reports vary), more recovery time is needed. This prolonged period of recovery is most-often characterized by persistent fatigue, headache, sensory sensitivity, and difficulty focussing, and is referred to as persistent post-concussion syndrome (PPCS). It is very difficult to predict who will experience PPCS. One University of Pittsburgh study of high school football players found that players who reported on-field dizziness at the time of injury were six times more likely to experience a prolonged recovery (>21 days). Otherwise there appears to be no relationship between the nature of symptoms initially experienced and the duration of PPCS. Youth who fall into this category will likely be assessed with a full neurological and neuropsychological exam and, as outlined below, may benefit from a progressive rehabilitation program.

Return to physical activity and sport

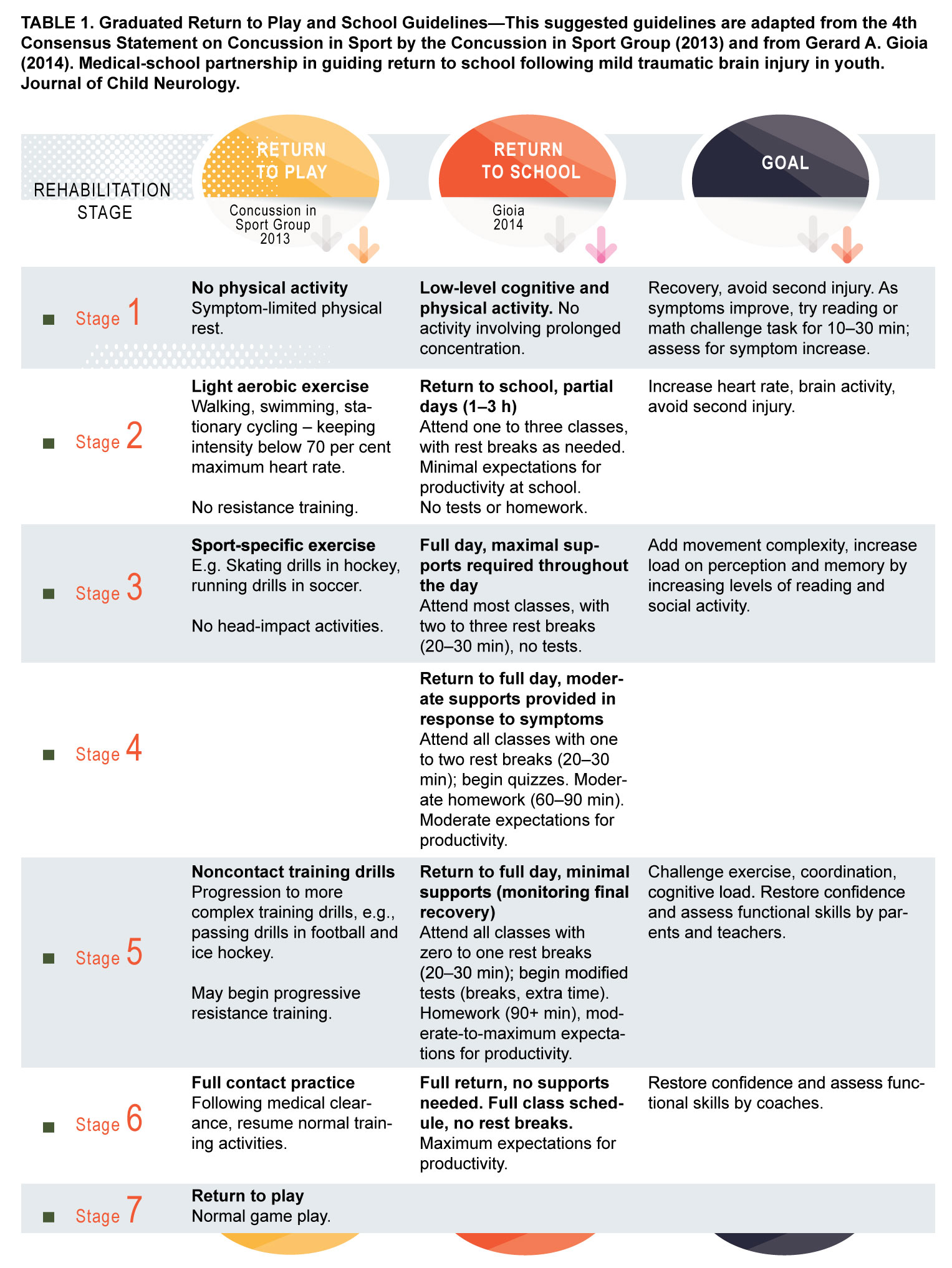

Once a youth is diagnosed with concussion, then there is a clear, week-long return-to-play (RTP) protocol recommended by the 4th Zurich Consensus Statement on Concussion in Sport (see Table 1). The RTP guidelines recommended by the Zurich Concussion in Sport Group (Zurich group) outline a progressive, stepwise approach to concussion rehabilitation. The recommendation is that each step will take about 24 hours and that the protocol will be complete in about a week. The student-athlete will undergo progressive challenges at each step and be monitored for the return of symptoms in the face of each challenge. If symptoms do return, then the student-athlete reverts to the previous protocol step until symptoms subside and then return to the

next challenge.

One of the motivations for the RTP protocol is the particular vulnerability that adolescents seem have to Second-impact syndrome (SIS), a rare but devastating condition triggered by a second concussion sustained before the symptoms of a previous concussion have resolved. If an adolescent experiences a second head-impact injury while recovering from a previous injury, in some rare cases, the brain can very quickly enter a state of medically-uncontrollable swelling, leading to unmanageable increases in intracranial pressure, and profound, life-long brain damage, if not death. SIS was cited as the cause of death for 17-year old Rowan Stringer, an Ottawa-area rugby player who sustained three concussions in less than a week. Although she was still suffering from headache as a result of a prior concussion, she continued to play a scheduled game, went down after a particularly hard tackle, and lost consciousness moments later. She never regained consciousness and died four days later.

Although there are clear dangers associated with failing to heed the RTP protocol outlined by the Zurich group, not every teenager will be vulnerable to SIS, and at this time, it is impossible to predict when and for whom it will strike. SIS, however, can be avoided by following the RTP guidelines, and this fact has been recognized in the US with the enactment of state laws like the Zackery Lystedt law in Washington. Zackery’s law requires that (1) boards of education develop concussion education programs for their personnel, parents, and students, (2) parents sign and submit a written concussion screening form every year before their child begins competition, (3) students suspected of sustaining a concussion be removed immediately from practice or play for evaluation, and (4) student-athletes diagnosed with concussion submit written medical clearance before returning to play. In Ontario, Rowan’s law (championed by Rowan Stringer’s family and friends) will be introduced in the Fall 2015 legislative session to establish an expert advisory committee to develop a very similar law here.

Return to cognitive activity and school

In contrast to the clear and largely-accepted guidelines for return-to-play, there is no one accepted set of evidence-based guidelines for return to full cognitive, social, and school activities. Students who have suffered a concussion are strongly encouraged to rest immediately after the injury. Rest includes taking time off from physical activity, including non-contact activities such as physical education classes, extracurricular dance, and vigorous physical play. Rest also includes reducing mental activity and stimulation, such as attending school, reading and writing, taking exams, socializing with friends, using a computer, or playing video games. Although studies have shown that moderate levels of rest during the first week after concussion are associated with faster recovery, there is growing concern in the rehabilitation community that resting for too much time post-concussion may do more harm than good in those who suffer persistent symptoms. The Montreal Children’s Hospital uses an assessment and rehabilitation program that is focussed on building resilience in youth with PPCS through a series of progressively challenging physical and cognitive activities. Typically-recovering students are assessed a week after their concussion with a physical and cognitive exertion test to ensure that they can handle cognitive and exercise stress without experiencing symptoms. Children who continue to report symptoms four weeks after their concussion receive a full neurological and neuropsychological assessment, and are enrolled in a graded rehabilitation program that includes daily aerobic exercise (walking or stationary bicycle), coordination exercises in which the child practices skills from their favourite physical activity, and visualization exercises in which the child imagines themselves enjoying their favourite activity or sport skill. The child’s concussion symptoms continue to be monitored and parents receive support and education about recovery timelines and coping strategies. The program is still under evaluation, but so far the results are promising.

With regard to return to school, rehabilitation professionals emphasize the importance of communication between health care providers, parents, teachers, and guidance counsellors. The school personnel most closely involved with the student should be given clear expectations about the timeline of recovery. Once the initial symptoms have subsided, the student should be permitted to return to school with the understanding that accommodations may be necessary. Those accommodations may include spending fewer hours at school, taking rest breaks during the school day as needed (where a rest break is defined as a time when the student is not engaged in schoolwork, reading, games, or conversation), being exempted from or being provided with more time to take tests and write assignments, and reductions in computer time and reading. Symptoms and school performance should be monitored to ensure that regression is avoided, and educators should be encouraged to raise flags if school performance does not quickly return to its former level. Gerry Gioia, a paediatric neuropsychologist at the George Washington School of Medicine, recently proposed a graded return-to-school protocol, and it is outlined in Table 1. Like the RTP protocol, these steps describe the recovery of a typically-recovering student and are expected to be completed in about a week. Along with these graded steps, Gioia recommends that schools establish concussion teams who help to manage and support recovery in conjunction with the student’s parents and physician.

Finally, a word on prevention. The hard truth is that concussions are difficult to prevent, mostly because they happen unexpectedly. While head-gear and helmets are very effective at limiting the severity of head trauma (i.e. they dissipate blunt forces and prevent skull fractures), they cannot prevent the brain from shaking inside the skull. Some evidence suggests that sport players who can ‘keep their head up’—that is, players who are well-practiced and well-rested so that they have the skill needed both to play their role and anticipate the play of others—are better able to absorb the bumps of contact sport. As Eugenie Bouchard has demonstrated, however, concussion can happen anywhere. As a mom of two hockey-playing boys, I believe it is important to balance concussion risk against the benefits provided by sport when making choices about participation. As always, education and preparation are the best defence against the negative impact of concussion.

For further information you may wish to read the following sources used in the article:

Concussion in Sport Group (2013). Consensus Statement on CONCUSSION in Sport—the 4th International Conference on CONCUSSION in Sport Held in Zurich, November 2012. Clinical Journal of Sport Medicine, Volume 23, pages 89–117.

Michael W. Kirkwood and Keith O. Yates (Eds; 2012). Mild Traumatic Brain Injury in Children and Adolescents. Guilford Press: New York.

Gerard A Gioia. (2014). Medical-school partnership in guiding return to school following mild traumatic brain injury in youth. Journal of

Child Neurology.

(1) In this article, the term concussion always refers to a mild concussion unless otherwise stated.

Leave a comment