It’s all about that space

Empty schools are less a liability and more an opportunity

Over the past decade one of the most confounding problems for our provincial education system has been the question of what to do with all this excess space and these underutilized schools? There are two interrelated variables increasing the vulnerability of our neighbourhood schools: declining enrolment and a rigid, unresponsive funding formula that continues to calculate maintenance costs on a fixed square-foot-per-enrolled-pupil basis.

What we are experiencing at this critical moment is another ebb tide of declining enrolment in our publicly funded schools. With fewer children in our schools, the pressure is on to reduce government commitment to the funding of schools for all. The common-sense notion is that the demand for school space is down and surplus inventory should logically be discarded. Through this lens, school sites are seen primarily as property, a disposable public asset and a potential public liability if they do not yield a return on their investment. Schools have no place in neighbourhoods too small to supply a large enough clientele to make them viable. Rural schools likely could never survive this kind of market-driven thinking and larger urban areas would find it difficult to express a local community’s democratic desire for their small neighbourhood school to exist.

The parent organization People for Education has documented how this thinking has come down hard on Ontario schools in recent years. It issued a report on school closings during 2009–2012 that documented 172 school closures and a further 163 reviews were still in progress. Over the past three years, the largest school board in Canada, the Toronto District School Board, has been faced with the prospect of an unimaginable 220 possible school closures. This even rivals the Conservative Harris government era in which massive public-funding cuts led to the closing of 250 schools.

OSSTF/FEESO sees the current trend of enrolment decline as both a challenge and an opportunity. In our submission to the Declining Enrolment Task Force, a number of useful and practical recommendations were made that could lead to thriving elementary and secondary schools with lower class sizes and comprehensive services.

The OSSTF/FEESO submission included the following: “Student distribution and school configuration must be considered above political, religious and union demands to provide a sound education for all. Having access to all schools in a geographical area and the freedom to create configurations that respond to enrolment and demographic shifts is essential to responding to this dramatic enrolment drop. A school of JK to Grade 8 students may be the best fit in one area of a school board and a Grade 7 to 12 school may serve the board in another area.” In addition, current curriculum increasingly requires specialized equipment and teachers with specialized education and training, consequently making these Grade 7 to 12 schools attractive. The current practice of bussing a student past one half-full school to attend another half-full school must end.

We should take this opportunity to maintain funding during the enrolment decline and allow all classes to shrink in size without loss of programs.

Fix the flawed funding formula

It is clear that declining enrolment will create shortfalls in funding for local school boards because the funding generators are based entirely on student enrolment. The government has the opportunity to support student achievement by removing enrolmentas the central funding criterion in many of its grants. Ideal school size has long been studied using many variables such as program diversity, sense of community and extracurricular opportunities, in addition to others, to determine an ideal student population. The ideal secondary school size is generally accepted to be below 1,000 students. Unfortunately, many secondary schools in Ontario were built to house numbers beyond that. School boards should not be penalized by having to pay to maintain and run a larger facility with fewer students. All parties understand the significant benefit of lower class sizes on student achievement. We should take this opportunity to maintain funding during the enrolment decline and allow all classes to shrink in size without loss of programs. The existing staff would support much more than the students in their classes.

Saving our public spaces through community hubs

School boards must resist the obvious and easiest path in response to declining enrolment, which is simply to make drastic budget cuts and/or close schools. After starving boards year after year and forcing them to reallocate resources away from certain sites, trustees often face the unenviable task of closing the local school. Each of the current 72 boards is, in one way or another, grappling with the same dilemma. While one solution cannot be imposed from above, some short-term relief can be found from the bottom up. The school is and will continue to be the hub of the community. It is considered the safe, comfortable centre of activity in a small community or the fixture in a neighbourhood of a larger urban centre. In many cases, the economic viability of the area is directly reliant on the existence of that school. It is often the most appropriate location for facilities that the greater community depends upon.

A number of years ago while touring Brazil for our Common Threads curriculum resource, Hungry for Change, our team was thoroughly impressed with the way schools had been built to integrate a variety of services that residents counted on. The local elementary school in a small town also housed the town library, national tax-payment department and the municipal public-health office. In the rear of the school, a community garden thrived and provided produce for the school lunch program. Attached to the front of the school building was a local produce food stand and artists’ co-operative selling homemade arts and crafts. Many levels of government shared one school building that acted as the centre of the wheel with many extending spokes.

In Canada, the term “community hub” has recently become a politician’s dream. It is the ultimate in ambiguity and can be spoken by social democrats and liberals alike referring to schools in their local riding. But what do we really mean by the term and how can it save some of our schools from closing or being sold off? Certainly, the notion of strengthening ties between schools and services to their surrounding communities is not new. Community use of schools and parental literacy initiatives can be traced to the early 1920s in rural communities in Canada, the U.S. and Mexico. Education pedagogical leaders such as John Dewey, Celestin Freinet, Anton Makarenko and Paolo Freire have written extensively on the school as a community focal point.

David Clandfield, author, educator and former school board trustee, was an advisor in the Rae government, looking at integrating services within schools in the early 1990s. He recently edited a collection of global experiences in School as Community Hub: Beyond Education’s Iron Cage (ourschools/ourselves, summer 2010).

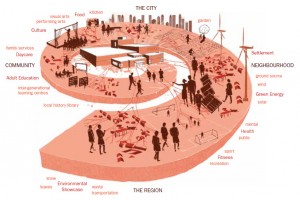

In the opening chapter, he situates hubs along a five-point continuum, extending from the basic community use of schools to the fully integrated school-community relationship, from the simplest form of permitting eligible community groups to book school space for use after hours to the co-location of community services within a single plot of land that may house a school or daycare, a parenting centre, adult education classes etc., and be funded by not only the school board, but also by the local municipality. Clandfield argues that the proper relationship of a school/community hub goes beyond rationalizing services and the use of space. It requires us to imagine a different community school: the Two Way Hub, “one where children’s learning activities within the school contribute to community development and when community activities contribute to and enrich children’s learning within the school.” He states, “This does not mean that the school dilutes its commitment to the development of critical literacy and numeracy or to the phased development of higher-order critical thinking over the years of compulsory education. It does mean that what the community has by way of knowledge and skills flows into and across a curriculum based on really useful knowledge—engaging its students in understanding and changing the world.”

Clandfield claims “the full community hub will yoke the interactive neighbourhood school with the multi-use hub to produce a kind of ‘new commons’ where education for all, health, recreation, poverty reduction, cultural expression and celebration, and environmental responsibility can all come together to develop and sustain flourishing communities on principles of citizenship, co-operation and social justice. This is how our schools can become a bulwark against the principles that would reduce them to factories producing skilled elites, compliant workers and eager consumers in a drive to achieve competitive advantage and measurable prosperity in the world of neo-liberal globalization.”

There are options to closing schools —it’s a question of political will

There are options to closing schools —it’s a question of political will

Once elected as premier, Kathleen Wynne issued mandate letters to each of her ministers in September 2014. Included in the orders to the Minister of Education, Premier Wynne asked select ministries to work together to develop a policy on community hubs. The message was quite simple: “use some empty school space across the province for community resources—or community hubs that could be supported by creative partnerships.” It can be a school, a neighbourhood centre or another public space that offers coordinated services such as education, health care and social services.

Initially, the Minister of Health and Long-Term Care and the Minister of Municipal Affairs and Housing were asked to consult with community stakeholders to design a policy that supports the development of these community hubs. We continue to watch this development and hope that in the short term, the ministers will freeze any further school closures or sales rather than make it necessary for boards to hand over schools in the most desirable locations to developers. It’s the right thing to do. After all, these are our public assets.

ILLUSTRATION: Aaron McConomy colagene.com

Leave a comment