Shining a light on the list

Has Ontario’s “Sunshine List” outlived its relevance?

This spring, while addressing the press about the release of the 2016 Ontario “Sunshine List,” the annual list of public sector workers who earned more than $100,000 the previous year, Ontario Premier Kathleen Wynne said, “Is $100,000 a lot of money? I think it is.” Twenty years after its inception, the Sunshine List continues to be a media-hyped opportunity to scrutinize the wages of Ontario’s public sector workers. The problem, though, is that it’s more likely now than ever that you may find your neighbours, or even yourself, basking in the list’s sunny glow. It’s a bit of an annual hunt for many to see if they know anyone on the list—recreationally checking in on the financial status of our friends. Not only voyeuristic, the act leads to judgment, divisiveness, and derision amongst the workers of our province.

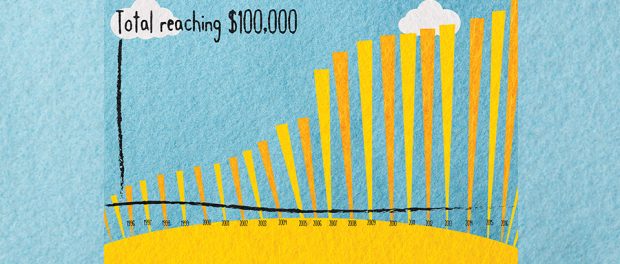

The number of names on the Ontario Sunshine List has grown each year, thanks to the fact that the $100,000 cut-off has remained unchanged since the list’s inception under Mike Harris in 1996. In its original visioning, the Public Sector Salary Disclosure Act sought to disclose the highest public sector earners and to increase public confidence in Harris’s Conservative government. However, 20 years later, the purpose, validity, and relevance of the list, and its threshold, need to be critically examined. The history of the list, as well as its stagnant benchmark of $100,000, means it now creates a much different outcome and effect than it did in its infancy.

According to Statistics Canada, the Consumer Price Index (CPI) increased by 44.4 per cent between 1996 and 2016. This means that a 1996-equivalent threshold for the Ontario Sunshine List today would be an income of $144,430. The simple act of adjusting the threshold as the CPI increased would have reduced the number of names on the list today by 82 per cent, from 123,410 to 22,138.

Looking at the numbers in terms of education workers helps put things in a bit of perspective. With the current $100,000 threshold in place, many top-category teachers are close to making the Sunshine List; if they were to do summer school, have a specialized position with extra compensation, or earn any kind of retro pay, they would easily break the barrier. In 1996, the top category for most teacher salary contracts in Ontario was significantly lower. In Toronto, for example, the top salary was about $65,000.

The list is a “totally different measure now, but it would be politically unpopular to change,” suggests Dr. Raymond D. Dart, an Associate Professor in the School of Business at Trent University. “It should always have been indexed [to the CPI], but public employees are always an easy target.”

OSSTF/FEESO Member Karen Stewart (District14, Kawartha Pine Ridge) echoed Professor Dart’s sentiment. She says, “We already have to defend ourselves in public, and I’m concerned people will question me more when we reach the list. I want to know how to respond. I believe that our taxes should be used to create good services, schools, universities, roads, and hospitals.” Stewart’s fear is common among public service workers whose jobs would not even have come close to making the list when it was first initiated. The 2016 list includes teachers, police officers, nurses, principals, and professors. The face and character of the Sunshine List is changing rapidly, and that change is driving more and more people to question the validity of the list and its current threshold.

Along with the Sunshine List’s original intentions of transparency and accountability come unintended outcomes, most especially because of the lack of CPI indexing. The expanding membership on the list leads to a scapegoating of those professions whose levels of compensation have been protected through the work of their unions and federations, and have often simply kept up with the rate of inflation. At the same time, the private sector has rushed to limit levels of compensation and security for its rank and file workers, while increasing the wages of its CEOs and other top earners—but the Sunshine List draws the focus away from this wage gap. We end up with a scenario where shame and blame cards get political leaders points in the media, while the focus on public-sector compensation continues to force a wedge between the province’s workers. Perhaps this is exactly what the Wynne government is seeking. We are now shaming the very professions that have historically been honoured and respected—workers who serve the public good, like nurses, police, firefighters and educators.

Professor Dart’s belief is that the political nature of wages has changed, partly because we’ve seen such a large-scale escalation of top-level private sector wages: “Twenty years ago the worry was about growing public sector wages. Now we have private sector wages that have grown much more rapidly, but at the same time we have the growth of precarious and fragmented employment. So we have significant wage gaps between public and private sectors, but we are still looking at the size of public salaries. Our focus needs to be elsewhere. Of course reviews of public spending are good, but we need to instead look at how employment security is destabilizing and unraveling.” He suggests that, rather than looking at the Sunshine List as a negative, it needs to be framed as a “desired state of employment.” He further suggests that it is the responsibility of those of us who are approaching, or have exceeded, the $100,000 threshold to engage in solidarity work and social justice activism. We need to advocate for those whose jobs and wages are destabilized by the increasing gap between private sector wage-leaders and the precarious, fragmented workers.

It’s true that education workers are an easy target; most of us have strong job protections, the prospect of a healthy pension, and good benefits. However, the quality of our working conditions also gives us a responsibility to stand up and proclaim, “This is what a fair wage is!” With the advent of increases in Ontario’s minimum wage and in the wake of the $15 and Fairness campaign, perhaps the Sunshine List will become a call to arms amongst education workers, drawing us to advocate for fair wages and benefits for all of Ontario’s workers. Rather than allowing the list to divide workers, it can act as a catalyst for solidarity.

So, yes, Premier Wynne, perhaps $100,000 is a lot of money, but no one should be shamed simply because their wages have kept up with inflation. There is no shame in professionals earning a professional salary. The shame is in the huge number of working people in Ontario who are still not earning a decent, living wage.

Thanks for finally talking about >Shining a light on the list –

Education Forum <Liked it!